Joe Cirincioni, the former president of the Ploughshares Fund, in an article titled “Can We Prevent Nuclear Catastrophe during the Trump Administration?” got to the nub of the problem. Funding for anti-nuclear work has been drying up, he said, because “Donors appear skeptical that non-government organizations can motivate meaningful change in nuclear postures. Why give money to groups that cannot show any impact?”

And that’s the problem. After 78 years of trying, what do we have to show for our work? The fundamental rationale for keeping nuclear weapons remains largely intact. The nine nuclear-armed states are upgrading their arsenals, expanding their arsenals or both. We’re in a second nuclear arms race.

I think we need a new approach. Seventy years of arguments built around fear and morality have failed to eliminate nuclear weapons. And despite years of dedicated, thankless work by anti-nuclear campaigners, no practical roadmap, short of a dramatic change in human nature, has yet been found for reaching elimination.

But there is a promise of something new. After decades of work re-examining the facts surrounding nuclear weapons (and the associated myths masquerading as facts), RealistRevolt has created a new line of argument that is being called a “stunning, breakthrough.” It is an approach that puts the elimination of nuclear weapons squarely within the realm of realistic possibility.

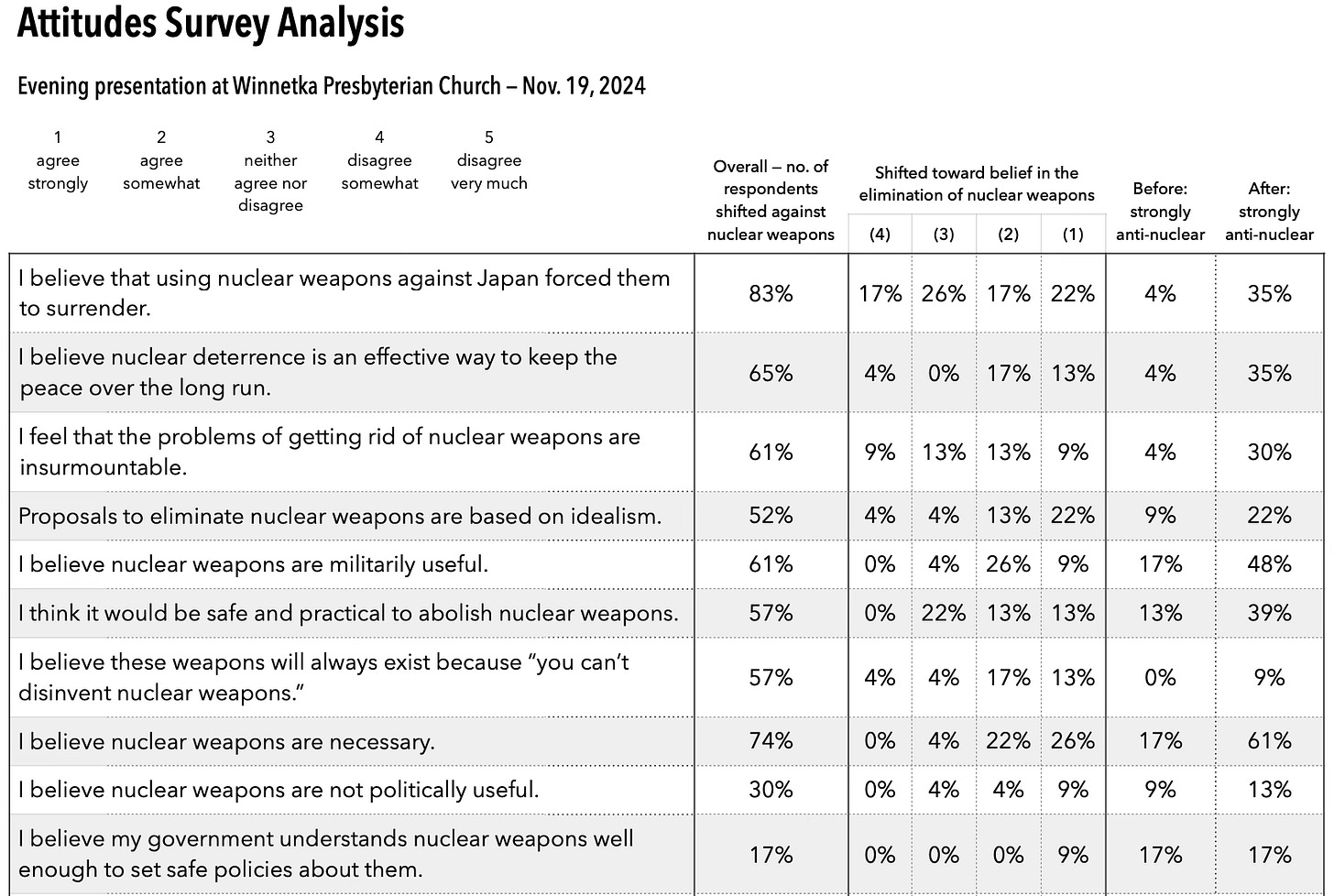

The proof for this claim is in the numbers. For the last several years, RealistRevolt has surveyed audiences about their attitudes toward nuclear weapons before each presentation we do, then presented arguments from It Is Possible (the book that dismantles some of the assumptions that undergird nuclear weapons policy), and then surveyed their attitudes again after the presentation.

The before and after results are astonishing.

But before I tell you about the results, let’s talk caveats. The sample size for the entire dataset is only a little larger than 200 respondents. We will have more confidence in the results once the sample size is larger. And the sample isn’t random. Obviously, some people in the audiences came to hear the talk because they already oppose nuclear weapons.

But neither of these objections affects what’s really startling about these surveys — the movement. No matter where people started before the talk, what’s remarkable is how many people were moved away from their original views to new positions, and how radical those shifts were. The shifts away from pro-nuclear toward anti-nuclear are remarkable. There is clearly something going on here. Given the seventy-plus years of futility, the promise of a new pathway to elimination — even with caveats — deserves a closer look.

I haven’t yet compiled all the data, but let me give you the key takeaways from the latest survey:

The arguments worked broadly. After the talk, on most key issues, 50 to 70 percent of the audience had shifted. Some shifted more, some shifted less, but they still shifted toward opposition to nuclear weapons.

The arguments worked on all comers. They moved the views of people who started out favoring nuclear weapons as well as people who opposed nuclear weapons.

The arguments sometimes made radical change. In some cases they completely reversed people’s beliefs, in other words, took them from strong belief to strong opposition to nuclear weapons in a single sitting.

Let’s look more closely at some specifics. One of the key “facts” that “proves” that nuclear weapons are “war-winning weapons” is the claim that the use of two atomic bombs at the end of World War “shocked” Japan’s leaders into surrendering. When asked to agree or disagree with the statement, “I believe that using nuclear weapons against Japan forced them to surrender,” 83% of respondents shifted away from their initial belief and toward disagreement with that claim. Some shifted a lot, some only a little. But given how intractable beliefs about nuclear weapons are, it is remarkable to see an argument that can change the views of such a large proportion of the audience.

It is rare for people to completely change their view. So the shifts that some people experienced from one end of the spectrum to the opposite end are remarkable. And when the issue in question is one that is widely accepted throughout society, one that is the foundation for a country’s national security policy, that is almost unheard of. Yet after hearing the talk, 17% percent of the audience shifted all the way from one end of the five point scale to the other, starting at “agree very much” that the atomic bombings won the war, and ending up at “disagree very much.” It is a stunning shift.

And if you take those 17% whose views were totally flipped and add in the 26% of the people whose views were shifted 3 points (either from “agree somewhat” to “disagree strongly” or “agree very much” to “disagree somewhat”) the total of the audience that experienced a major shift in their views on this question rises to 43%.

At the start of the talk only 4% said they disagreed very much with the statement that Hiroshima forced Japan’s leaders to surrender. After the talk? More than a third — 35% — said they disagreed strongly that the bombings won the war.

There were surprising results for other fundamental tenets of nuclear weapons belief. When asked before the talk how they felt about the statement, “I believe nuclear weapons are necessary” only 17% said they disagreed very much. Once the talk was over? A whopping 61% — more than triple the original number — said they now disagreed very much that nuclear weapons were necessary. Again, a remarkable shift on one of the core beliefs about nuclear weapons.

Another foundational assumption about nuclear weapons is that they are “the ultimate weapon.” So it is not surprising that when the audience was asked before the talk what they thought about the statement, “I believe nuclear weapons are militarily useful,” only 17% disagreed strongly. When asked after the talk, however, that percentage had more than doubled — almost half the audience now strongly doubted that nuclear weapons have military utility.

The takeaway from all of this is that the pragmatic arguments from It Is Possible appear to generate real support for anti-nuclear weapons work. They change minds in ways that haven’t been seen before on this subject. True, these are only the results from the most recent survey. I’m still in the middle of collating, cleaning, and analyzing ten more years of data. I hope to have more evidence from that larger dataset in the near future. But these results were so remarkable, I wanted to share them with you right away.

For many years my intuition told me that there was an underlying disquiet in the United States about nuclear weapons. Polls, too, have seemed to say the same. In 2019, for example, a poll of American millennials found that 58.5% said they believed a nuclear weapon would be used somewhere in the world in the next ten years. Even though Americans don’t talk about nuclear weapons, fear of nuclear war still lurks somewhere in their minds. But somehow that fear hasn’t translated into action.

What would happen if Americans had a reasoned, factual, pragmatic set of arguments that undermined the fundamental rationale for keeping nuclear weapons? What would happen if they could be sure that nuclear weapons weren’t the ultimate weapon? What would happen if their friends and neighbors shared these beliefs, if people met regularly to talk about the issue, to support and sustain each other? What would happen, in other words, if there were a real mass movement promoting these pragmatic objections to nuclear weapons?

What these results hint at is that there is a revolution out there, waiting happen. What they are whispering softly to us — if we will only listen — is that our days do not have to be framed by deeply suppressed but still ever-present fears that someday nuclear war will come.

What are the views of people in the eight other nations that have nuclear weapons?

This appears to be arguing that because there are indicators that more Americans don't like nuclear weapons, the US should get rid of them.

That says nothing about the deterrence element of a viable nuclear weapons arsenal. Or what happens if a nation voluntarily disarms when hostile nations do not.